A successful 40th anniversary for SFJO

The two-days celebration of the SFJO’s 40th anniversary took place on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, at the beautiful and historic Marine Station of Endoume, exactly where the SFJO was founded 40 years ago, on the initiative of its Honorary President, Professor Hubert Ceccaldi of the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes.

The aim of this event was to take a retrospective look at the history of the SFJO and its development, to discuss the ongoing evolution of natural environments in interaction with human activities, and to map out directions and themes for the future, with a particular focus on involving the younger generations.

After words of welcome from Dr Thierry Pérez, head of the Endoume Marine Station, Dr Patrick Prouzet, President of the SFJO, recalled the main objectives and achievements of the organisation over the past 40 years. Mr. Hervé Menchon, Deputy Mayor of Marseille in charge of marine environment and biodiversity also gave a presentation (see below),

followed finally by the Consul General of Japan in Marseilles, Mr. Hiroshi Kitagawa (see address below).

The Honorary President of the SFJO, Professor Hubert-Jean Ceccaldi, reminds us of the major milestones in the SFJO’s 40-year history and discusses avenues for the future.

After a detailed description of the high significance of the SFJO logo, he gives an overview of some of the major technological progresses in Japan’s maritime activities, such as the systematic installation of artificial reefs in coastal areas, and the ‘Chikyu’ deep-sea drilling vessel. Other developments and common practices have been addressed during the Franco-Japanese colloquia organized alternately in France and Japan. Among the most prominent institutions contributing to cooperation between the two countries, the Maison Franco-Japonaise in Tokyo, which welcomes French researchers in all disciplines and hosts the Franco-Japanese Society of Oceanography of Japan, has a place of choice. Several research themes are underpinned by the concept of ‘satoyama’, later extended to the sea under the term ‘satoumi’. These concepts encompass a wide range of themes likely to guide the future activities of the SFJO and its Japanese counterpart, including demography and migration, the resilience of socio-ecosystems, environmental protection, education/training for all stakeholders, the value and rights of living organisms, and the ”maritimization” of terrestrial environments.

Following this doubly groundbreaking speech, several congratulatory messages and good wishes from the Japanese parties were given via video messages from the President of the SFJO Japan, Professor KOMATSU Teruhisa, the President of the Satoumi Research Institute, Professor MATSUDA Osamu, and the President of the Fisheries Research and Education Agency of Japan, Dr NAKAYAMA Ichiro.

Satoumi and the blue economy – links, questionings and possible activities for the future

Patrick Prouzet reminds us of the need to bring together environmental, economic and social aspects to promote sustainable development, while including cultural elements. Such a convergence requires negotiation between the parties involved, as the environmental dimension is generally ignored while priorities given to the socio-economic importance. This imbalance inexorably leads to the disappearance of wetlands, intensive use of pesticides, degradation of the quality of coastal waters, unsanitary conditions of oyster farming areas, etc., with deadlines for improvement objectives constantly being postponed. Facing this situation, we need to adopt a more global approach to minimizing the ecological footprint of each use within the framework of a global environmental governance.

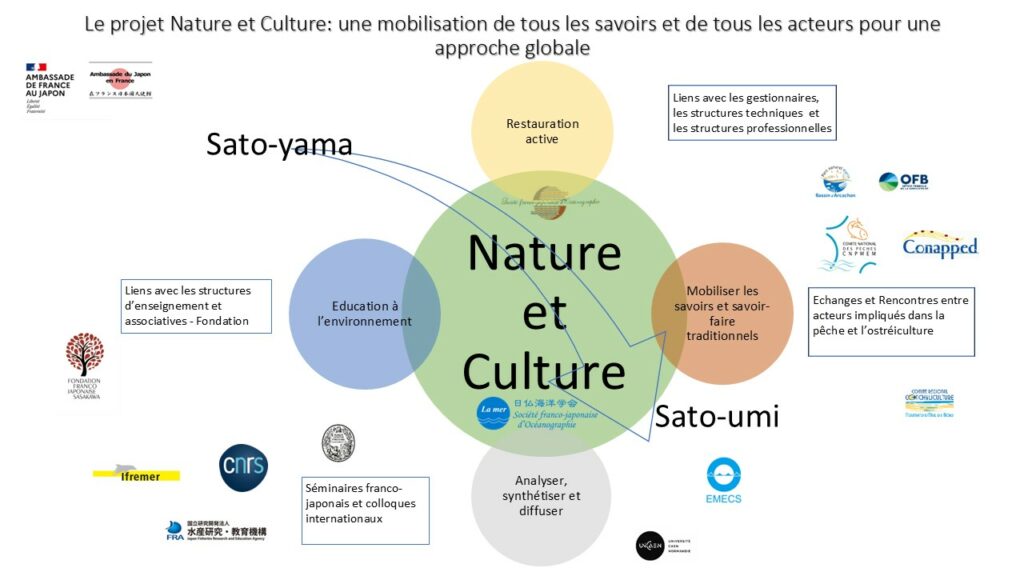

As mentioned above, cultural diversity ‘defined as the expression of the knowledge and practices of different local communities and their traditions’, must be taken into account. At the beginning of the 20th century, Tanaka Shozo was already talking about ‘satoyama’, later further developed by works such as those of Kenji Imanishi, who presents nature as ‘a living being at the heart of which we have always been nourished, alongside a myriad of other creatures’. Much later, in 2008, Tetsuo Yanagi proposed the new term ‘satoumi’, or the ‘active restoration of a coastal zone with high productivity and high biodiversity’. All these developments form the basis of the SFJO’s ‘Nature and Culture’ project in relation to the activities it is developing, as shown in the presentation below.

Following this introduction to the SFJO’s Nature and Culture project, Jean-Claude Dauvin gives a concrete example of its implementation at the geographical scale of the Channel, a ‘shallow megatidal coastal sea’, comparable in some respects to the Seto inland sea in Japan. He refers to the ‘japonization of the Channel’ in relation to introduction of foreign species: 152 reported since 1900, including 54 species originating from Japanese waters, the two most famous being the Manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum) and the oyster Magallana gigas (formerly named Crassostrea gigas), both deliberately introduced for the development of clam and oyster farming. It should be noted that the latter has become so well established that it is now colonizing rocky areas on a massive scale, as in Blainville sur Mer on the west coast of the Cotentin peninsula. Regarding unintentional introductions, J.C. Dauvin cites the perforating polydoran worms studied in collaboration with a Japanese professor, Waka Sato-Okoshi from Sendai University.

As in the case of the Seto Inland Sea, he points to the high degree of anthropisation of this sea, itself an area of cooperation with the UK that “Brexit” has unfortunately weakened. He nevertheless reminds of a succession of European projects that have led to a strategic vision for the Channel area, including integrated coastal zone management (ICZM). In short, this vision is quite like that of the ‘Basic Plan in Ocean Policy’ adopted in Japan. At a more local level, he takes the example of a multi-stakeholder consultation and involvement process initiated in the early 2000s to develop an environmental vision for the Seine estuary. The issue of climate change and its impacts has also been addressed, with the creation of the Normandy IPCC.

Despite all efforts however, the system remains highly fragmented and sector-based, with a plethora of initiatives and structures, not always well connected. The other challenge is the growth of the blue economy, when it comes to the expansion of offshore wind farms, within the strategic framework of coastline development and the associated governance system.

In conclusion, the Channel, a regional sea, is a maritime area that is conducive to integrated management and sustainable development, combining science (knowledge of natural environments and the impacts they are submitted to) and society (culture, perceptions and practices), but much remains to be done and invented for the future of this common good.

‘Think global, act local’ is what Yves Henocque reminds us in his presentation, which begins with the global and local narratives of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). At the root of this narrative, the health of marine (SDG 14) and coastal (SDG 6 and 15) ecosystems, influenced by climate interactions (SDG 13), determines the ecosystemic services that are beneficial to human activities (SDG 8). This is the background against which our landscapes and seascapes are set, at the very heart of the satoyama/satoumi concept as promoted by the Satoyama Initiative launched internationally by the Japanese government in 2010. A landscape should not be perceived as immutable but instead as changing in response to the dynamics that govern our socio-ecosystems. It argues in favor of a ‘lived nature’ rather than an ‘idealized nature’ that one would like to keep under wraps. Satoyama/satoumi is not a fixist concept; on the contrary, it envisions ever going interactions and adjustments in the fragile balance between ecosystems dynamics and human activities.

In this respect, one of the tools used in the Satoyama Initiative, but ignored in most countries including France, is the OECM (Other Environmental Conservation Measures) included in the famous 30% protection target to be reached by 2030 adopted at the COP15 in Montreal. An OECM is not similar to the French MPA (Marine Protected Area) in that it is a zone where biodiversity is actively protected in the long term, particularly the so called “ordinary biodiversity” because it does not feature emblematic organisms. The other tools developed as part of the Satoyama Initiative are indicators, designed to reflect the characteristics of the satoyama/satoumi concept: diversity of landscapes and seascapes and protection of ecosystems; biodiversity (including biodiversity linked to agriculture); knowledge and innovation; governance and social equity; activities and well-being. Unlike the top-down process that generally prevails in the creation of an MPA, the OECM follows a much more ‘bottom-up’ process involving local decision-makers, users (including in private sector), operators and the public at large, in a form of local ‘nature and culture’ project carrying messages of regional and national scope.

This first part of the meeting, aimed at providing a framework for the presentations and discussions that followed.

Art of science, science of art – Evolution of marine biodiversity and the impact of human activities

Thomas Changeux began by arguing that a historical approach to ecology is both interesting and necessary. This is the origin of the ‘Biodivaquart’ project (Aquatic Biodiversity in Art), a multidisciplinary project applying digital ecology methods to biodiversity data from ancient figurative works of art. The project involves collecting works of art according to date, location, realism of animal representation, and of course the author. From that starting point, a collaborative process of species identification is carried out with the help of specialists of specific animal groups. Statistical analysis then enables to estimate the space-time variations in species abundance according to representations in the paintings. A global finding is a general decline in the representation of fishes, particularly freshwater species, and a general increase in the representation of crustaceans and mollusks, which can be attributed to fishing pressure or environmental degradation, but also to changes in eating pattern.

It is therefore possible to use works of art to gain a better understanding of the historical evolution of aquatic biodiversity, by distinguishing between what is determined by the ecosystem from the effects of technical and socio-cultural filters. Paintings displayed in this perspective can produce an aesthetic shock and thus raise awareness among the general public. A one-day international study convention also emphasized the highly multi-disciplinary and multi-activity nature of this type of approach, involving archaeology, art history, science history, historical ecology, as well as fishing and culinary practices.

However, Anne-Sophie Tribot wonders whether how for most of us, the only way to imagine the marine environment and its living creatures is through the media. Indeed, the media experience gives a feeling of connection with nature, and will influence our practices. To evaluate an aesthetic shock, tools can measure attention and visual exploration and compared with photography, a work of art turns out to be more stimulating for the perception and thus for the integration of knowledge at the junction between nature and culture.

Artist Mauro de Giorgi gives an example of his artistic experience with the Japanese practice of ‘Gyotaku’, which consists of creating an imprint of a fresh fish using Chinese ink, a practice used to immortalize fishing catches.

Did you say biodiversity? But which biodiversity are we talking about?’ asks Charles-François Boudouresque. For the general public, biodiversity is a bit of a magic word with beautiful images and friendly animals. The general public thinks in terms of species, whereas ecologists need to know what species are present and how they interact within the ecosystem. In fact, there are key species, ecosystem engineers, not forgetting of course the so-called heritage species which, depending on their status (friendly, emblematic, threatened, rare, etc.), will be the subject of management measures. C-.F. Boudouresque gives the example of the dolphin which, a century ago, was a harmful species to be eliminated, but which has since become eminently sympathetic and worthy of protection! He goes on to talk about ‘luxury biodiversity’ and its excesses, where we end up wanting to eliminate one species in the name of conserving the other, as if they were not both part of the same ecosystem. This is how we end up creating true ‘animal parks’ on sites such as the Salins d’Hyères or the island of Porquerolles. In the name of maintaining ‘friendly’ species, aren’t we over-protecting them to the detriment of the balance of the natural ecosystem? And yet the diversity of species and their habitats within an ecosystem is essential to its proper functioning. Is there not a risk that Posidonia or Coralligenous will become the ‘luxury biodiversity’ that must be protected at all costs, while neglecting the many other species and habitats that are not so emblematic? The distribution of research efforts and conservation measures can be a good indicator, as shown by the example of Spain (2003-2007) where mammals and birds are over represented while fish, amphibians and reptiles account for only a small proportion of research and conservation efforts.

Similarly, an analysis of the European Union’s conservation programs shows how heavily biased they are towards ‘luxury biodiversity’. Many species, whether they are on the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) red list or not are neglected, as is the case of the hammerhead shark in the Mediterranean. On the other hand, we protect seagulls and the marsh frog which are proliferating and becoming a major threat to other species.

In conclusion, one must not forget ‘ordinary biodiversity’, the biodiversity that makes ecosystems work, particularly the ‘invisible biodiversity’ such as plankton in the water column, bearing in mind however that by protecting emblematic species, we are indirectly protecting ordinary biodiversity. From a human-centric approach, then a species-centric approach, we must move resolutely towards an approach centered on the socio-ecosystem.

The end of the first day was marked by a reception at Marseille city hall, where the participants were welcomed by Aurélie Biancarelli, deputy mayor in charge of education, research and student life. In her speech, Aurélie Biancarelli emphasized the importance that the city of Marseille and the Aix-Marseille metropolitan area attach to marine research and the protection of maritime areas. Her speech was followed by a message of thanks from the President of the SFJO, followed by a speech from the Honorary President of the SFJO and a message from the Consul General of Japan in Marseille, who expressed his satisfaction at the many contacts and friendships that exist between the SFJO France and Japan and their many partners.

Marine and submarine landscapes – Perceptions and reconciliation with life

Didier Réault, President of the Parc National des Calanques, describes the history of the park with respect to its acceptance and ownership by the stakeholder, and how the park works with these same stakeholders. Then Alexandre Meinesz reminds of the drastic changes that affected the landscape through the artificialization of the French Mediterranean coastline. More than 5,300 hectares have been destroyed by 1,050 structures reclaimed from the sea. In Nice, more than 100 m have been reclaimed from the sea. In Monaco, 90% of the seabed between 0 and 20 m depth has been destroyed. However, these examples pale into insignificance when compared with the massive reclamation of the Seto Inland Sea in Japan. In the light of this massive artificialization, A. Meinesz drew up a hierarchy of damage to the marine environment, distinguishing between two targets: marine life and mankind, bearing in mind that climate change will worsen the impact. Remediation measures include continuous beach accretion or construction of perpendicular groynes, which are disappearing as the water rises, as in the Camargue region. Everywhere, rockfill dykes and protective walls, even when heightened, are threatened in the long term. So wouldn’t it be a long-term solution to build very large dams? The ‘Mose’ Dam of the Venice lagoon can be taken as an example, but the truth is that even this solution is likely to be temporary, submersed very quickly (water level), and is very expensive (3 million Euros each time the dam is put into operation). The Netherlands offers much longer-term solutions with the construction of dykes up to 32 km long. In all, 200 km of dykes have been built with hydraulics closings.

In 2008, the Delta Commission predicted +1.30m elevation of sea level by 2100 and +4M by 2200, as a result of which 400km of dykes have been heightened . Other examples can be found around the world, including the dam on the Thames river in England, the Samangeum dam in South Korea and the Marina Barrage in Singapore. Another gigantic project is resurfacing: the closure of the Straits of Gibraltar, as imagined in the pre-war Atlantropa project, to create huge polders. Today, this idea of damming up entire seas is spreading everywhere: the English Channel, the North Sea, the Baltic, including the Northern European Enclosure Dam (NEED) between the coasts of Cornwall and Brittany (161km!). Whatever the case, sea levels are rising fast and we’re going to have to find solutions other than those we know today to preserve environmental goods and services as well as our material possessions.

Jean-Charles Lardic, former head of the city’s environment department and initiator of the Artificial Reefs in Prado Bay project, believes that under current local authority governance, such a project would not have been possible. Even back then, it took a great deal of entrepreneurial freedom and teamwork to get the project off the ground.

Sandrine Ruitton then reported on the monitoring carried out on the reefs in Prado Bay, highlighting the undeniable reserve effect and the interactions with fishing activities.

Another topic of discussion: industrial activities and underwater landscapes, in this case the cable routes that criss-cross the oceans, as presented by Eric Delort. In the Prado area alone, no fewer than fifteen fiber-optic cables are arriving. The map from the French Navy’s Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service shows the cumulative anthropogenic footprint made up of wind farms, energy export cables, artificial reefs, pipelines and fiber-optic cables. But what ecosystems is this anthropogenic pressure being exerted on? Primarily Posidonia meadows and canyons. This raises the choice of cable installation route, a compromise between a straight line, the path through benthic biocenoses, the presence of other cables and the necessary distance between them (twice the height of the water), and the location of the beach chamber. In the deep zone, the cable is not buried in the water; it will be increasingly buried as it gets closer to the coast. Monitoring 18 months after installation shows how quickly the cable has colonized the landscape, and that it has virtually disappeared. In the final analysis, the anthropogenic pressure of cables on the environment, although very numerous, is less significant than one might think, with no need for restoration. The visual impact is of the order of a pencil line, preserving pre-existing underwater landscapes.

Observation/restoration of coastal and marine environments and sustainable fishing

Laurent Blanc from the city of Marseille (foresight/citizen participation mission) introduced the subject by emphasizing the city’s ‘open governance’ practices. He fully endorsed Jean-Charles Lardic’s comments on the need to change forms of governance, citing a number of initiatives, including the creation of a ‘Citizens’ Assembly of the Future’ to debate openly and continuously social issues such as sobriety in water management, the “city-nature” and citizen democracy.

Echoing this need for citizen participation, Laurent Debas tells us about two citizen science projects, ‘Biolit’ (observation of the quality of coastal environments) and ‘Pelamed’ (revitalization/reappropriation of traditional collective local fisheries management organizations, the Prud’homies). He stressed the need for official recognition of these citizen observation and management efforts so that, little by little, they can also feed into new forms of governance of coastal and maritime environments. Christian Decugis (head of the Prud’homie de Saint-Raphaël – Fréjus – Les Issambres), a professional fisherman, added to this by talking about sustainable fishing that respects the environment and the resource. In Europe, the main way of achieving this is through ‘maximum sustainable yield’, which means ‘the maximum quantity of fish that can be caught from a stock under existing environmental conditions without affecting the reproduction process. In 2024, it is estimated that 20% of the fish caught in France will still not be fished sustainably. In the Mediterranean, more than a hundred species are fished by 1,400 boats, but only around twenty of them are monitored. The sustainability of a fishery depends above all on using the right gear in the right place, at the right time and in the right way. From this point of view, the role of the prud’homies and the territorial management that characterizes them is essential to the sustainability of small-scale Mediterranean fishing.

Speaking of the monitoring of fish stocks and fishing carried out in the MPAs of the Southern Region, Laurence Le Direach reported on the existing situation, i.e. just over 5,000 ha under effective protection. She points out that the rate of full protection in the territorial waters of the French Mediterranean coast is very low, at 0.35%. Monitoring is carried out by visual dive counts and scientific fishing, as in the case of the Cap Couronne Reserve. In the Cap Couronne reserve, the average yield per 100 m of trammel net has increased fourfold in 29 years. However, the pressure remains high, with 66% of gear set on depths of less than 40m. In the Calanques National Park, in almost 10 years (2014-2023), there has been a significant difference in biomass between ZNP (Natural Protected Area) and non-ZNP, as well as an increase in the proportion of high trophic level predators in the catches. By visual counting, this last feature is even more accentuated in the case of the Port-Cros National Park where, after 50 years of protection efforts (including the professional fishing charter), piscivores now account for a significant proportion of all fish species, a change that is therefore taking place over a long period of time. However, L. Le Direach stresses the financial difficulty of maintaining long observation series.

In addition to the technical aspects (fish counting, scientific fishing, reporting tools and vessels), it is essential to share knowledge, pool resources and consult with managers and fishermen.

The last speaker was Thierry Thibaut, who introduced the concepts of restoration and inter-species balance. In the Mediterranean, the most common seaweed/habitat is Ericaria brachycarpa, which is threatened by the proliferation of sea urchins linked to the disappearance of their predators. This is leading to an irreversible shift in the ecosystem, where herbivorous fish such as the Salema porgy will multiply (40 to 50% of the biomass of teleosts in the Bay of Marseille). Reserves such as Port-Cros can have a perverse effect by encouraging an increase in herbivores that are no longer controlled because they are protected, with an irreversible decline in long-lived species. The imbalance in the environment can lead to over-grazing, with any attempt to replant (seaweed and Posidonia) doomed to failure.

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVES

Since 1984, when the Franco-Japanese Society of Oceanography was founded at the Endoume Marine Station, a large number of seminars, colloquia and meetings have been organized in both France and Japan.

This is the main characteristic of the two societies, which have organized 19 international events in France and Japan, with the 20th to be held in Japan in 2025. These events have covered a wide range of subjects: aquaculture, fisheries, general oceanography, recruitment determinism, biotechnologies and, in recent years, topics linked to risk and disaster prevention (the 2011 Tsunami in Japan), the impacts and effects of climate change on coastal and terrestrial ecosystems, and the development of offshore wind farms.

The organization of symposia and meetings has enabled links to be forged with numerous French and Japanese universities, research bodies, scientific and technical structures, professional organizations, associations and foundations. This is undoubtedly the foundation on which the two companies must build if they are to survive and contribute to the body of academic and traditional knowledge and, above all, to the syntheses needed for a less sector-based vision than is usually practiced in the management of environmental goods and services.

Since 2017, the date of the 17th Franco-Japanese oceanography symposium in Bordeaux, the definition of a ‘Nature and Culture’ project validated by the two SFJO France and Japan has enabled us to refocus on one theme: adaptation to change, which will be central in the years to come.

This can only be done within a framework of minimizing the ecological footprint of all uses, by taking into account not only ‘luxury biodiversity’ covering emblematic species, but also by looking at all the practices for conserving and promoting a biodiversity that is less talked about but which is just as essential to the proper functioning of ecosystems.

This adaptation to change will be based not only on academic knowledge, but also on local knowledge, taking care to respect the stakeholders for whom the productivity of aquatic environments is a matter of daily subsistence, and to preserve our natural and built heritage for future generations.

Aware that our natural environment is constantly changing, we need to work to reduce our ecological footprint by developing our practices and forms of governance at all levels.

It is therefore through a systemic, multi-actor approach, within a local framework, that we must work to reinforce this notion of sustainable, fair and equitable development, of harmonious development between natural balances and human activities for current and future generations.

Like its Japanese counterpart, the Société Franco-Japonaise d’Océanographie France contributes, and will continue contributing to bring together stakeholders, to disseminate multi-disciplinary work and to produce summaries produced by established researchers with considerable experience and distance in their own field.

In this context, the dissemination of events organized by our two organizations is a major factor in our recognition by the world of academic research. The partnership with Springer (165,000 downloads per chapter of the 4 conference proceedings published by this international publisher) and the publication of the journal La Mer, dedicated to Franco-Japanese work in the field of oceanography, must be continued.

The SFJO France website: 67,000 visitors, 830,000 pages visited in the last 5 years, shows the interest that our society arouses.

We are also recognized for our ability to bring together a wide range of players, including research institutes, universities, associations and foundations, professional technical bodies and educational establishments.

This has given us recognition at the highest level: the French Embassy in Japan, the Japanese Embassy in France, the Consulate General of Japan in Marseille, the Sasakawa Foundation and the Maison Franco-Japonaise in Tokyo.

Our links with communities of French and Japanese stakeholders – fishermen, shellfish farmers, including oyster farmers – in a context that goes beyond mere technical assistance and focuses on human relations and mutual support, enable the SFJO to organize Franco-Japanese meetings in a climate of trust and sharing.

We now need to better structure our relations with the world of teaching and education so that we can play a greater part in ‘the instruction and education of young and old alike, and show them the richness of our ancient identity’.

This will also involve forging closer links with our colleagues in the Social Sciences and Humanities to better integrate the concepts of participatory science and action research, not forgetting continuing our scientific relations in oceanography, including physical oceanology.

Finally, in the context of adapting to change, including climate change, it is important to forge closer links with the world of industry, in the name of their social and environmental responsibility, to promote innovative solutions, particularly on the basis of the satoyama-satoumi concept, which in the medium term defines the common horizon for the two SFJOs.

Our next meeting will be in Japan in 2025, in the town of Toba, in the prefecture of Mie, a region famous for its cluster divers and the cradle of pearl farming. There we will meet our Japanese colleagues for the 20th Franco-Japanese Oceanography Symposium.